Bridges

by Ed Madden

The men sitting at the blue table are talking about a new bridge. Taylor says that they have been talking about the bridge for forty years, but it may actually happen now. The doors to the wide porch facing the sea are open, a strong evening wind pushing through the house. The city of Salvador is a thin glimmer across the Bay of All Saints, like a string of tiny lights on the eastern horizon. It is after dinner, midsummer, Christmas just days away, the end of 2019. The Brazilian newspapers have just reported that a consortium of Chinese state-owned construction and railway companies has been selected to design, build, and operate a bridge that will cross the bay from Salvador on the mainland to Itaparica, this island. The contract won’t be signed for another year.

It will be a toll bridge, Taylor says. Everyone will have to pay to cross. We are sitting in the large dining room of the Instituto Sacatar, an artists’ residency devoted to intercultural understanding through creative practice. The artists have gone to their studios, their rooms, just a few of us left at the table. Any moment now, one of the night guards patrolling the property will come by and lock the gate that opens to the beach, a little strip of sand under the trees bordered by a small sea wall, a tidal creek.

There is already a bridge on the other end of the island, the Ponte do Funil, where the southwestern bulge of the island almost touches the coast, near the mouth of the Jaguaripe River. The proposed bridge will be just over seven and a half miles long, high enough at the center to allow ships to pass beneath. The project will require more than 13 miles of new expressway to cut through the island to the Funil Bridge at the other end, bypassing the urban area of Vera Cruz, where the passenger ferries from Salvador currently dock. It will cut travel distance and time—quicker than the hour-long ferry ride, trucks crossing the island rather than driving around the bay. Taylor says the bridge will make the island no longer an island. He does not mean geography.

*

We called it Algoa Road when I was growing up, the small unpaved road that runs east-west, cutting through ditched farmland and river bottoms in lower Jackson County, Arkansas, to connect Highway 145 South to Highway 37. As it crosses that part of northeast Arkansas, the road passes by soybean fields and rice fields and the house where I grew up, and after a couple of hard turns crosses the Cache River, ending up at the little town of Algoa. In the 1990s, the names of these little county roads became numbers to better enable 911 emergency designations. Still unpaved, Algoa Road is now Jackson Road 30. Algoa is just a few houses—fewer after the last tornado—a small church, and weedy lots of parked farm equipment.

Where Algoa Road crosses the Cache River, the Cache is more slough than river. When I was growing up, the bridge was maybe a couple of hundred feet of clattering boards, no rails and only one lane wide. No traffic could meet on the bridge. Going west from the bridge you could see where people dumped trash on either side of the road, the bags splitting open, plastic and glass bottles floating out in high water. To the east, where the woods ended, someone kept a few hives of bees. When I brought friends home from college, we would drive down to the old bridge across the Cache River, park on the road’s thin shoulder and walk across. They said it looked like something from a movie. We sat on the bridge, letting our feet dangle over the slow river made of time and water. We would graduate soon. We were already the past that we would be. Sometime after I left, while I was in graduate school, the bridge fell in and the road was closed.

Only one way in, one way out

*

Fabio says that he loves Catú because it is the end of the road, only one way in and one way out. Nothing happens here, he says; it’s safe. Everyone knows everyone. We are going to lunch with Augusto. Augusto says most of the homes here are summer homes for families from the mainland. The road to Catú on the east side of the island is difficult, a washboard of ruts and gouges and loose sand. Fabio says that when it rains the road can become impossible to drive. He drives slowly. We pull to the side to meet a man and a boy on horses coming toward us, the man following the boy.

The village is so quiet. We are the only ones in the café. We drink cervejas by the water. We can see the mainland from here, not far at all. The Funil Bridge is around the bend. The afternoon settles in, stretches across the lawn. The town seems deserted except for the waitress who serves us moquecas com ovos. Fabio, whose family raised cattle, is vegetarian. Fabio says a French couple owns a section of the forest just outside of Catú, that they want it to stay undeveloped. They can’t keep people out, he says, though they want to. The locals cut wood to use, hunt animals there to eat.

Augusto says they can’t keep it the way it was.

*

“It’s all water under the bridge now,” my uncle said, talking about his dad, dead a decade. We were having dinner at On the Border, one of those big garish Mexican restaurants near the interstate where everything is bright, loud, fake. The waitress handed us thick laminated menus. As she flipped through the pages, my mother quipped that you had to get through a lot of liquor to find the food. He had taken us out for dinner, taken us out to get away for just a moment from the hospital, where my dad had been diagnosed with cancer, a moment to eat something other than hospital food. I wondered what he meant, though I knew something of the bitterness back then, a tension between brothers, that old story.

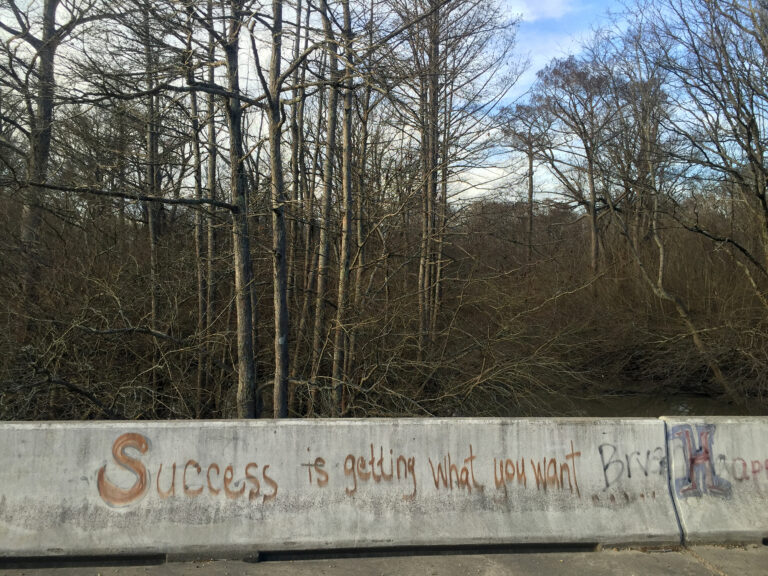

When we got home from the hospital a few days later, I learned that the old bridge had been rebuilt, cement, new. After I had come out to my parents as a gay man, years before, I didn’t go home for over a decade, another old story—the difficult letters, difficult words. The old bridge had fallen in. Now there was this new one. My parents no longer lived on a dead-end road. I drove down there later, discovered it scribbled over with graffiti—some tags, some names, somebody loved somebody. Someone had sprayed Success is getting what you want in very careful, almost cursive, orange.

My father died three months later, after we had taken him home.

I crossed the old bridge in my dreams every night, a bridge to the past.

*

Among the blue and white tiled scenes in the cloisters of the Igreja São Francisco in Salvador—each scene a Bible story or moral allegory—time is a thing with wings, an angel, a fairy. It flies over, holding a solar clock like a lantern. Each scene is framed by elaborate images of plasterwork, at the top of each a cartouche displaying a Latin maxim. On this one: Volat irrevocabile tempus. Time flies.

Four figures walk below the winged figure, single file, the allegorical ages of man. A child leads them, his arms stretching toward the bay where there are boats waiting. A youth lifts a basket of wheat. A man, ripe fruit tucked under his arm, scratches his ass. The old man at the back, bent on a cane, carries a censer of incense. A snake swallows its tail on the ground at the child’s feet, as if to remind us that time can be both cyclical and linear, the long walk to old age but also the harvest, the fruit and wheat. The four ages walk in a straight line, left to right, and they walk away from us, old age nearest, childhood far ahead, looking away. To read left to right is to go back in time.

In the outer courtyard, all of the scenes are proverbs, many about wealth or time or death. In the adjacent passages of the cloister the scenes are all biblical, though the figures are white Europeans (the tiles made in Lisbon)—Jacob wrestling an angel, Elijah fed by the ravens, Moses lifting the stone tablets to smash them, people dancing in the distance around a golden calf. The tablets in Moses’s hands look like massive tiles. Around the corner, the walls of the altar and nave are slathered in gold.

Volat irrevocabile tempus. Time flies irrevocably, says a small card of translations affixed to the wall below. Die ziet vergeht unwiderruflich. Le temps vole irrevoacablement. El tiempo vuela irrevocablemente. O tempo voa irrevogavelmente. Even though a friend and classics scholar assures me that a neuter adjective can be used as an adverb, I want to read it as “time flies irrevocable” or “it flies, irrevocable time.” Irrevocable, not irrevocably, that feels more sobering. Not that time flown by is irrevocably gone, water under the bridge, but that time, which is irrevocable itself, flies. The past has flown, is gone. The tiles, the azulejos, are old, crazed with tiny cracks, some protected by netting as if at any moment they might fall from the walls.

Jacob and the angel are just lifting their hands to one another as if about to dance. Another angel grabs the knife in Abraham’s lifted hand by the blade, seizing it perpetually in midair, while Abraham clamps his other hand forever on his son’s neck. Throughout the cloister time is frozen. The ravens hover, the bread forever almost delivered to the prophet’s hand. The whale is always vomiting Jonah onto the shore, tiny creatures on the sand all around him, a crab, a sea urchin, a scatter of shells. Moses lifts the commandments into the air like Atlas holding the world up forever.

The blue and white angel of time carries a solar clock. Its wings look like paper money.

*

Contrato assinado! When the contract for the new bridge across the bay was signed on November12, 2020, Rui Costa, the governor of Bahia, tweeted: Chegou a hora da ponte Salvador-Itaparica deixar de ser sonho pra virar realidade. It’s time for the Salvador-Itaparica bridge to stop being a dream and become a reality. In 2014, one journal had dubbed the long-discussed project “a bridge to the future.”

“Itaparica’s development had been stunted,” announced China Daily. “So, the new bridge is expected to transform the island into a transportation center connecting northern and southern parts of Bahia.” Bahia is the northeastern Brazilian state where Salvador and Itaparica are located.

An engineer replied to Costa’s tweet. Em um Brasil parado, he wrote, in a stalled Brazil, Bahia will carry out the greatest work in the history of the nation. Parado, stalled or stopped, stagnant, stunted. Contrasted with the great work of a bridge, a maior obra, carried out. Carried over, carried through. Realized.

Among the other mostly congratulatory and occasionally anti-Chinese replies to Costa’s tweet, one critic asked about the environmental impact. E como ficou a parte ambiental? The bridge, he said, will cause siltation, will impact the benthic fauna and deforest significant green areas of the island. Benthic fauna, he explained, fauna bentônica, are the small creatures that live on the bottom among the sediments—bichinhos que vivem entre os sedimentos. Crabs, sea urchins, the scatter of shells.

After dinner that night in 2019 at the blue table, someone said the new bridge will allow for more efficient transportation of goods, three crops of soybeans grown in Bahia each year to be sent to China. They said the new bridge will cut travel distance and time—straight across rather than driving around the bay and quicker than an hour-long ferry ride. After dinner, I walked out to the pier at Sacatar, looked east across the bay at the lights of Salvador spangling the distant horizon.

*

The glow over the dark fields east of Newport comes from prison lights swabbing the sky. Built in 1998, the prisons—a men’s unit and a women’s—are one of the new industries that came to town after I left, like the steel processing plant built to forge railway steel in 2002. If you are driving north on Highway 67 at night, the lights of Newport shine to the west, the prison lights coming up in the east.

On a map, Jackson County stands on a fat square leg jutting down at bottom right, another leg kicking out to the left. The county looks vaguely like a pudgy man in a rumpled sweater and wide pants kick-stepping his way west. The White River is a blue squiggle entering the county from the west—right about where the pudgy marcher’s belly button might be—meeting the Black River at Jacksonport, then turning and heading south from Newport. If you zoom in on Google Maps, little commas of blue begin to appear along the river like cartoon shivers—curls of old channel cut off or overflow left behind. They’re called oxbow lakes because they look like yokes, the wooden beams put over and around an animal’s neck to help it drag a load. Over time, a river channel may cut through the neck of a meandering loop, leaving that little omega of channel behind. Sometimes the abandoned bits of river on the map look like parentheses or empty quotation marks, like something the river used to say. Or the way my parents and I once talked, before we stopped talking.

Running alongside the White River on the map is the bright yellow line of state Highway 67N, moving northeast across the county. The old highway, now Highway 367, still runs through Russell and Possum Grape and over Departee Creek before it crosses the river on the old blue bridge that sits where a river ferry used to run, drops traffic off in downtown Newport. The thin white line of that old highway, Highway 367—like a thread, like a ghost of a road—marks the old way to go, further west, before the realignment of 67 redirected traffic past those small towns and past rather than through downtown Newport, a way that is straighter, shorter, quicker.

This is not how we see the world, from above. We see it from the ground, from the roads and ditches and bridges. The prison lights glow in the east. The women’s prison unit houses a vocational school and the state’s death row for women. My parents led Bible studies there. My mother almost died in a car accident nearby, a man speeding down one road toward another, her car full of groceries and prison songbooks.

*

Of the two ferries that cross the bay from Salvador to Itaparica, the car ferry is larger, takes longer, about an hour. The passenger ferry, the lancha, takes about forty-five minutes and runs more often. When I first arrived in Itaparica, it was via car ferry. Augusto had three of us in the air-conditioned van, visiting artists headed to the Instituto Sacatar with luggage for the two-month stay—a playwright from Los Angeles, a painter from Madrid, and me, a writer originally from Arkansas. The other visiting artists from Athens, Saõ Paulo, and Salvador would meet us at the institute. We would not be in another air-conditioned van during the stay.

On the way to the airport to pick up one of the artists, Augusto sang along with Caetano Veloso. Quando o tempo for propício, Augusto sang, when the time is ripe, propitious——tempo meaning time in Portuguese, though also meaning rhythm, meaning weather. I sat between the driver and Augusto in the front seat, the vent hitting my face, Augusto singing beside me, Tempo, Tempo, Tempo, Tempo. Before we got to the airport, we stopped by a home goods store to pick up supplies for the island. There were signs all over the store for “Black Friday,” a sales strategy imported directly and without translation from the United States. I pointed out the Christmas decorations—artificial trees with fake snow, Mary and Joseph, the child, the angel, all very white. “Same stuff everywhere,” I said. Yes, said Augusto, “and all made in China.” Outside it was summer and brutal hot.

That night we first arrived on the island, in Bom Despacho at dusk, the line of cars for the last ferry back to Salvador stretched down the road. Augusto explained that it wasn’t just those who had been on the island for holidays but also a way to cut through from the south without driving all the way around the bay, a way to save time.

*

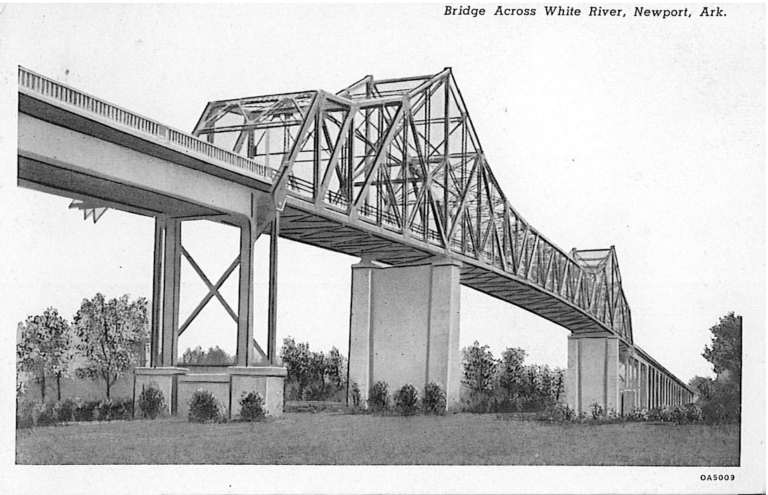

Robert, a friend from high school and local historian, sends a picture of two bridges, the new bridge being built over the White River and right beside it the old Blue Bridge, built in 1930, still in use for now. No one knows what to do with the old one. For a while there was interest in saving the “Blue Bridge,” listed in the national register of historic sites, but the city didn’t accept possession, couldn’t accept the cost, so now it’s destined for demolition.

When the railroad was coming through the county in the late nineteenth century, they wanted to cross the river at Jacksonport, a working river port a few miles north. According to state histories, the town refused permission to build a railway bridge, refused to grant right-of-way. So the railroad moved down river to the “new port,” business followed, and Newport replaced Jacksonport as the county seat in 1892. Little remains of Jacksonport but a pier, an old riverboat docked there for tourists, a museum. In the museum, you can see buttons made from mussel shells pulled from the bottom of the river, a thriving industry drawn from river silt until zippers and plastic killed the need for buttons made of shell.

When the bridge opened, Newport celebrated with a three-day festival and a parade. “Covered wagons represented the past,” my friend the historian writes. Tractors and farm machinery represented the present. “The future,” he says, “did not necessarily have to be represented in the parade; it was the bridge itself.” A bridge to the future. Nothing stays the way it was. We can’t really call it the Blue Bridge anymore, he emailed recently, as it is no longer blue, the state having years ago decided it wasn’t worth keeping up, the paint fading to pale yellow and cold sky and rust. The old riverboat in Jacksonport, the Mary Woods II, capsized in 2010, right there by the shore. When they tried to set it right, it fell apart. The train depot in Newport, built in 1904, is no longer a depot, though they call it The Depot. A renovated relic, people rent it for events—weddings, parties, family reunions.

Another high school friend says they wanted to make the old bridge a pedestrian bridge—walk over the river, walk back, just woods and fields on the other side. The blue arches lift an empty sky. The river flows slowly by, under the new bridge, under the old.

*

When an oxbow lake fills in with sediment and time, it may be different from the surrounding land. The soil may be different, the vegetation—the difference of what lies below sometimes evident in how and what grows. The scar of what happened is still there.

Where there’s a highway exit south of town as the highway passes it by, there’s now a big gas station. The last time I was there, it was midwinter; I saw my mother. I was filming the area with a photographer, who was struck by the long flat delta landscapes and far horizons, the fields going on forever. We stopped at the station on our way out. The field just beyond was filled with geese, end of the hunting season, the geese lifting up into their annual migrations. We were driving away from home. We were driving home.

Taylor said that one of the visiting artists at Sacatar asked children in one of the Itaparica schools, What is a good bridge? She asked them, What kind of bridge can we build between us?

*

With thanks to Taylor Van Horne, Augusto Albuquerque, Fabio Porto, Robert Craig, and Cindy Olson Mabry. Van Horne is cofounder of the Instituto Sacatar in Itaparica, Albuquerque the program director.

Sources:

Itaparica, Bahia, Brazil:

“A Bridge to the Future,” Grandes Construções, 21 May 2014.

“Chinese companies to build Brazil’s second-longest bridge,” XinhauaNet, 14 Dec 2019.

“Chinese PPP finally signed for $1.3bn Salvador-Itaparica bridge in Brazil,” Global Construction Review, 16 Nov 2020.

Contra o cidadão de bem [@Safadaceae]. “E como ficou a parte ambiental?” Twitter, 12 Nov 2020, 2:22 p.m.

—-. “Não mesmo? Vai fazer assoreamento, impactar a fauna bentônica (bichinhos que vivem entre os sedimentos) e ainda vão desmatar área verde em Itaparica.” Twitter, 12 Nov 2020, 4:43 p.m.

Costa, Rui [@costa_rui]. “Contrato assinado! Chegou a hora da ponte Salvador-Itaparica deixar de ser sonho pra virar realidade. Está documentado nosso compromisso com as empresas chinesas e agora temos mais trabalho pela frente. Vamos gerar emprego, renda e melhorar a vida de milhões de baianos! #Bahia.” Twitter, 12 Nov 2020, 11:29 a.m.

Engenheiro Cidadão [@jpesafi]. “Em um Brasil parado, a Bahia vai realizar a maior obra da história do Brasil.” Twitter, 12 Nov 2020, 3:34 p.m.

Nan, Zhong. “Chinese touch lifts infrastructure.” China Daily, 30 Nov 2020.

Newport, Arkansas, USA:

“Another attempt to transform Blue Bridge fails,” KAIT 8 [Jonesboro, AR], 17 May 2016.

Craig, Robert D. “Newport’s Blue Bridge,” The Stream of History, published by the Jackson County Historical Society (Newport, AR), vol 43 no 2 (June 2010): 1-27.

Originally from Arkansas, Ed Madden is a professor of English at the University of South Carolina, where he teaches Irish literature, creative writing, and LGBTQ studies. He is also author of four books of poetry. His poems have appeared in many journals, as well as in The Book of Irish American Poetry and The Forward Book of Poetry 2021. In 2015, he was named the inaugural poet laureate for the City of Columbia, South Carolina. In 2019 he was named a Poet Laureate Fellow of the Academy of American Poets and a visiting artist fellow at the Instituto Sacatar in Bahia, Brazil, a residency upon which part of this is based.

*

All photographs by Robert Craig and Ed Madden.

Dear Ed,

I read your work. So glad to know your about your background. It was very interesting.

Hope you are well and happy.

Cyndy Colbert