Mongrel Country

by Jane Carroll

The two-kilometre radius for exercise promised us a circle of more than twelve and a half kilometres in circumference to walk around.

Except that when we pulled out the map and looked, we found that our designated area was almost all eaten up by the sea, the full circle of permitted exercise reduced to a lopsided crescent. Our radius thrust out to sea, pointless. We made jokes about taking up swimming.

When space is limited like this, some people look outside, planning escapes to exotic destinations, yearning after forbidden and far-flung places. The limits drove my focus inwards, caused me to think not of what lay beyond our uneven crescent, but of what lay within it.

Besides, within that broken crescent lay one of my favourite walks, a route along a fragment of the north county Dublin coast that varies according to the weather and the time of year and to the sea and what it gives up or hides of the shore. Its changing nature allows this walk to become something different each time. Of course, the far edge of the allotted circle cuts it short, but I could live with that—two kilometres out, two kilometres home.

This is the walk along what we call the back beach. We use this walk daily, summer and winter. But my husband and I rarely go together. It’s not a walk that welcomes company. This stretch of coast is usually empty. So, in the margins of the day, I walk here with our mongrel dog and most days we meet nobody else.

There are two beaches here. In the weeks since the lockdown was announced, the front beach has become popular with walkers and joggers. For the most part these people stick to the paved paths around the seabanks, the band-stand park and the smooth arc of sand between the harbour and the banks. They send out tractors in the summer months to comb this beach, to make it neat and tidy and sterile. It’s a nice beach but it is tame. It has benches and an ice cream shop.

I ignore the front beach and skirt by the joggers and the walkers on the path around the seabanks, holding the dog in against the banks of pink valerian and green weeds with my thigh as they trundle past. He is a nosey animal, always watching to see if there are other dogs, if there are opportunities for mischief. Sometimes he’ll pretend to be engrossed in sniffing at the grass and then suddenly twist out into the path of a passing dog, jumping up, playful and enthusiastic.

Once we pass the seabanks, we reach a wide triangle of tarmac that tapers out at one point as it dips down onto the back beach, where the paved path runs down and out over sand and then, abruptly, ends.

This is the threshold. This is the point where most of the walkers turn back. This is the point that we press on.

I normally listen to audiobooks when I walk the dog but, at this point, I always take off my headphones. It has become a ritual, a way of opening myself up to the back beach. The stories from other places don’t fit properly here. I want to hear the place instead—the sough of the sea, the wind, the birds singing and crying out.

This is the back beach. I know that it’s also called the King’s Strand but I don’t know which king the name memorialises, nor know of anyone who actually uses that name for this place. In fact, there are no names on much of this land on the printed maps because for half the day this land is sea and needs no names or only gets unofficial ones made up by children. The names that have stuck have been used and worn smooth by generations of people from this place: King’s Strand, Tankardstown, Bell’s Strand, Bremore head, Bell’s Lane, Sailor’s Grave, Cromwell’s Harbour. Where once place ends and another begins is a matter of opinion.

I used to be afraid of this place. I’d heard stories—though now I’m not sure who told me these stories—about drownings and suicides and sands that shift unreliably underfoot and of a treacherous sucking undertow. Stories about the way waves could suddenly turn and roar back into the beach and sweep people off their feet, suck them out into the deep, cold water. When I was little, even the seals that slipped their faces up out of the water seemed somehow malevolent. Selkies watching out for husbands. For children to steal.

But all that fear never kept me away from the back beach. I’ve spent so long here that I’ve learned how to watch the tide and gauge when it will turn. I can tell with a skimming glance at the front beach how much of the back beach will be exposed above the water line. My body has adapted to it too. A childhood spent on and off the beaches around this part of the coast has given me precise balance and an instinct for which rocks stay steady underfoot and which will slip sideways and turn your ankle. An eye for changes in the weather, for rain coming in from the sea.

Our mongrel dog has adapted to it too. And as we approach the back beach he strains on the leash, eager and ready for this part of his walk. If there is nobody around, I let him off to run. He is easily distracted though, drawn to whatever moves around us—a bird, a crab, a walker in the far distance. Mostly he darts about, shoving his face into bundles of seaweed and piles of wet stone. His mixed nature has given him keen eyes and a lolloping gait that is almost elegant on the flat sand and comically awkward on the rocks. His slender hips bunch and slide as he clambers about, the narrow wedge of his head hunched down between his shoulders as he sniffs and sniffs and sniffs. Sometimes he drops his head to drink from the little nameless stream that tumbles out of a gap in the grass. He moves up and down until he finds the place that the water is more rain than sea, more sweet than salt. The stream that has been so compact and focused that it is all but hidden in the grass suddenly spreads itself out when it reaches the beach, like someone fanning their fingers out, not grasping but letting go.

I follow him. Arms wide for balance. Head up and watching for seals, for other walkers, for interesting things that the sea has left behind.

Sometimes the sea eats up the beach and doesn’t give it back until later in the year, suddenly spewing out sand and debris and flotsam on one winter afternoon. Other times, the sea spits out thousands of tiny shells, each no bigger than your littlest fingernail. The shells glitter the strand, pale purple and white, making the whole beach a lilac sweep. Sometimes the sea gives back a handful of Victorian pottery or a clutch of glass, worn smooth and milky by the water. Other times its gifts are less lovely: a hundred rotting dogfish, their empty gills gaping at the sky; the brown, spiny bodies of Christmas trees; a half dozen plastic boxes left in a delicate row, like strange offerings to the gods of the land.

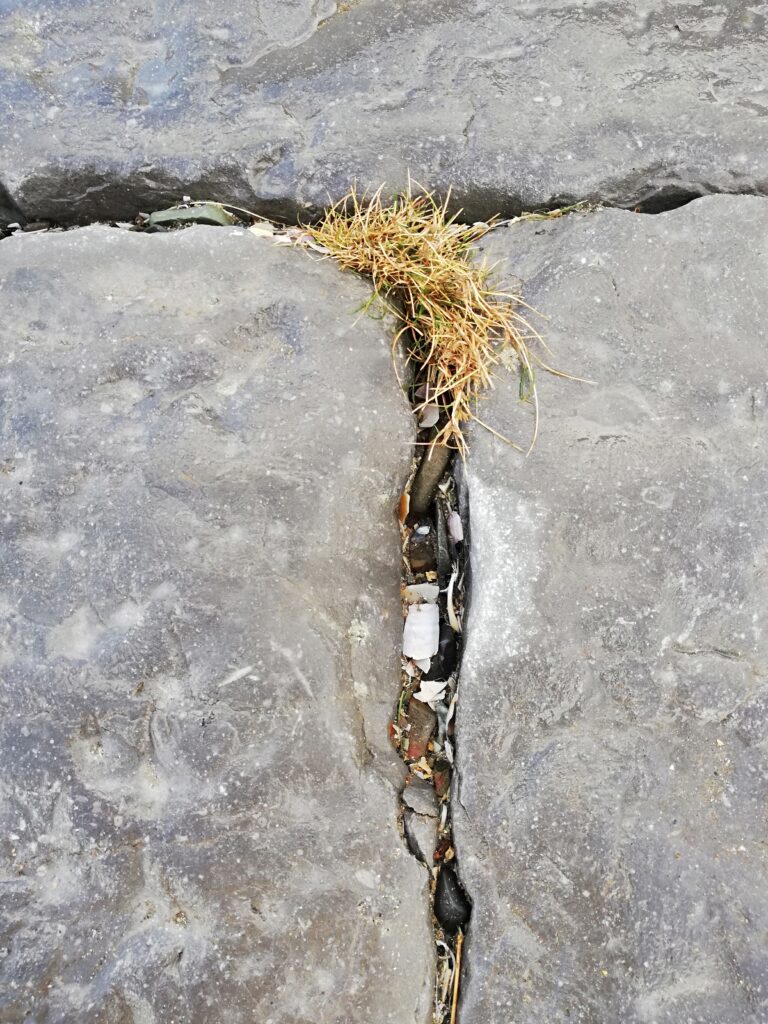

In all, I figure we are well matched for this place. Because this is a mongrel country—a place of mixed heritage and mixed use, crammed in on one side by the sea and by the railway on the other. In some places and at some times it’s barely thirty yards wide. In other places and at other times it spans almost a kilometre. This place fluctuates, changes, and reverses its changes twice over each day, the tide tethered to an unseen moon, dragged forward and back, forward and back. Just as the sea throws back odd assortments of things, history has thrown broken fragments of things together here too, broken open on the borders between past and present.

This part of the coast is full of ruins, full of partial places, all tumbled together, and though they once must have been a succession, a series, they now appear all together, all ruined, all part of the same past. Here is the red-brick chimney of a factory, its fireplace blocked up with grey stone. Here is the Martello tower, grey and stumpy and missing its top, its bottom clotted with valerian and the tiny purple flowers of ivy-leaved toadflax and grass. It’s difficult to imagine that this place was ever new, that it was ever anything other than a ruin. Right next to the tower is the place where there used to be bathhouses and boathouses, from when the town was a Seaside Town and not just a town beside the sea. You can still see the spot where the boardwalk sprang from, the iron nails crying out their red into the rocks around them. When I was little, the remains of the boardwalk were still there, a precarious tether between the sea and the land.

A little further along the back beach we pass the place where they used to burn lime, the remains of a stone kiln, a tumbled heap of dressed stones and the fragment of what used to be a window. The dog and I pause here. The dog sniffs at the air and at the stones, running his nose along the clumps of seaweed, looking for crabs, scratching at the coiled casts left by the sandworms. Those casts too are a kind of ruin, a trace of where something used to be, the shape for something that is not there anymore.

This place is alive with birds. Oyster catchers wobbling around the rock pools. Curlews—heard more often than seen with their thin piping call. Herring gulls and common gulls, clamouring and raucous. Colonies of cormorants, black as oil, their wings held stiff out at right angles, like old coats with the wire hangers left inside. The odd heron flying low over the waves, its shape huge and prehistoric. In the summer, swifts scythe out from their nests in the cliffs, out over the strand, hunting insects. Once, for a few weeks in the autumn, an egret, ghostly and elegant.

The dog makes little skipping runs towards the birds he sees, scaring them up from the sand. When he realises he can’t catch them and they won’t play with him, he turns his attention to the ground again. Sometimes he finds a crab and crunches it up. Once, he found a mermaid’s purse—the tasselled oblong pocket of dull brown fibre that is a shark’s egg—I didn’t realise what it was at first and, afraid he would choke, wrestled it from his mouth. It was wet—hot and wet with the dog’s spit and cold and wet with whatever was inside it. I was revolted. He was annoyed I had taken his prize and then just thrown it away. It probably wasn’t a shark’s egg at all, only a dogfish’s egg. A purse for a poorer sort of mermaid. When I was little, I used to worry that there were sharks in the water. I felt disappointed when I found out dogfish were a sort of shark. They seemed too small and ordinary. I’d seen too many of them washed up and rotting on the beach.

Some days the wind that comes off the sea is fierce. It peels tears from your eyes, rakes the hair from your scalp, stings your cheek with whips of sand. The waves come grey and loud and there is nothing except the roaring of the water and the air. And the keening of the gulls in the air, hanging like kites, balanced on the breeze.

We make our way along the back beach and over to the rocky outcrop that marks an unofficial boundary between King’s Strand and Bell’s Strand and the end of our allotted two kilometre limit. There is nobody here to stop us walking on, to stop us pressing forward on to the next stretch of beach. But we behave nicely, tethered by an invisible thread that pulls us backwards. Sometimes we walk back along the strand, tracing over our own footsteps, but usually I turn up along a narrow track worn into a hollow of the cliff, Bell’s Lane. It doesn’t look much like a laneway; it looks more like a desire path, a gap in the grass worn down into the landscape by the laziness of generations who will not walk around the cliffs to reach a proper designated path. I hook the dog back onto his lead at this point. I’m never sure what other walkers might be on the cliffs who may not be happy to see a lolloping mongrel.

In summer, the laneway is a tunnel between trees, hollowed out from the greenery. The air is heavy with pollen then and the seabirds give way to songbirds. Here you can spot wrens and bullfinches and goldfinches and bluetits and sparrows. Hear them too—dunnocks and blackbirds, robins, and woodpigeons. There’s a smell of piss and pollen. In autumn the laneway is clotted with bloody berries, hips and haws.

At the top of the track, we switch back along the railway line, passing now on top of the cliffs that border the back beach.

The cliff-top is close-cropped grass, marked out in rectangles for soccer and gaelic. In the margins of the playing fields there are rabbits. Sometimes I spot them, sometimes the dog sees them first, his head whipping up at the first sign of a white tail flashing in the grass. He has never caught a rabbit, but when he sees one he strains against me; his whole body trembles and his jaws open slightly, his ears flicking forward. Something urgent and primal stirs in him. He noses at their droppings sometimes, at the little tufts of fur left in the grass, and I wonder if he knows that these things are left behind by the fast brown animals in the verges. I imagine that he would chase them for the joy of running after them, as he does with the birds on the beach. Perhaps that is naïve. Perhaps he has been dreaming of eating them raw, of catching them and biting down on their quick little bodies since he first saw them. Perhaps this is what he dreams about when he lies on his bed at home with his paws twitching.

Our walks are not circular. They do not follow a smooth geometry. Though we walk the same spaces, the line of the walk is haphazard, jagged, broken by stops and starts, by the dog’s whims, by my pauses while looking at birds or turning over stones or the sea’s leavings with my foot. Some days the back beach is a wide sweep of sand with the sea turning its back on the cliffs. Other days, it is a narrow gauntlet between the ruins and the edges of the waves. All the words to describe our passage “through” or “across” or “along” or “beside” are inadequate because they are only ever partial. The back beach makes mapping redundant.

How could we map this place anyway? Should we set the coast line when the tide is in or when it is out? Do we take into account the weird high spring tides or the extra low ones that come in the height of summer when the whole town seems to smell of salt and seaweed and the haze that comes in off the water and burns off by noon? How can we take into account the mongrel way that history is blended up here, the way that time and place are churned together by the sea? Better, then, to do away with the fallacy of mapping, with the idea of transcribing neat lines over this landscape. Better to accept that each walk here will only ever reveal a fraction of the place, that it will never be a pure whole. Better to embrace the mixed nature of this place, to learn to be partial, to learn to be mongrel within it.

Jane Carroll is an assistant professor in children’s literature at Trinity College Dublin, where she usually deals with landscapes in books. She lives in Balbriggan and actually quite likes the seagulls.