Declan’s Murphy’s The Spirit of the River

Review by Cassia Gaden Gilmartin and Elizabeth Murtough

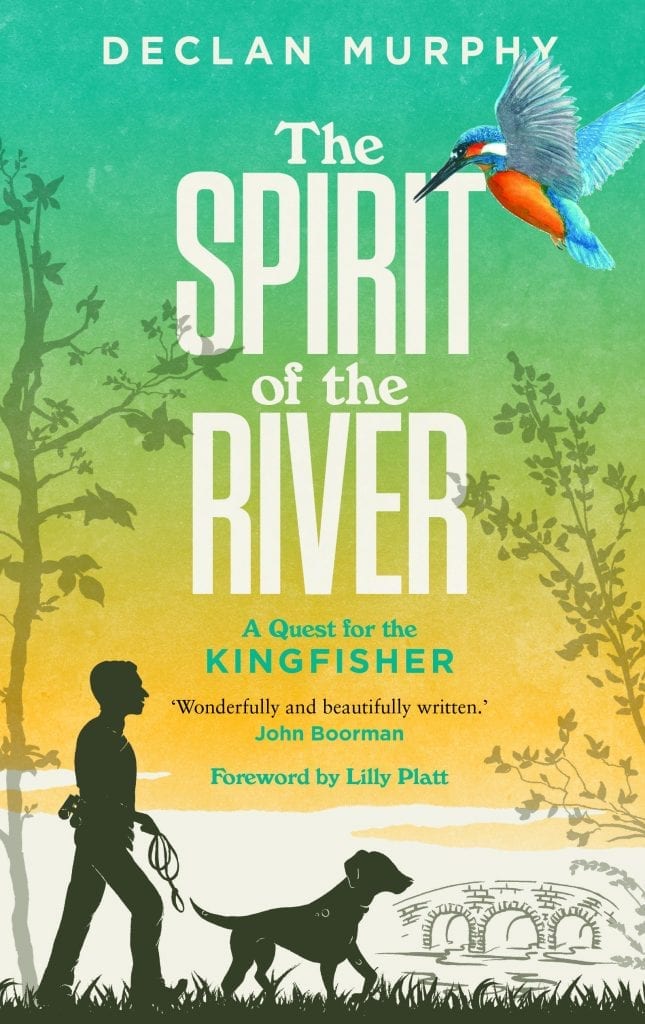

On the surface, Declan Murphy’s The Spirit of the River is a book about the author’s efforts to study the kingfisher during its nesting season—but the story that emerges in its pages, as the search for this elusive bird becomes entangled with other investigations of human and avian life, is something much more varied and rewarding.

The book is subtitled “A Quest for the Kingfisher,” with the language of questing—especially the mythical quest for the Holy Grail—recurring throughout. What’s most intriguing, though, is that the quests described aren’t defined by the journey-maker’s object of desire. In fact, the most rewarding quests appear to be those allowed to veer joyfully off-course. The search for the Grail, Murphy writes, was frustrated for so long because the searchers maintained a false certainty as to what they were searching for; it was in letting go of this certainty and embracing the journey that the knight Parzival discovered the true meaning of the Grail. Similarly, Murphy’s own quest is at its most fruitful when tangents and delays are welcomed—when he chooses to follow an unexpected bird downstream, or climb into the water to view his river from a new angle. “For me, the time spent looking and searching for any animal or plant is only part of the experience,” he writes; “the immersion of oneself in nature and its surroundings, and the indulgence of the senses, is the reward for the effort.” His work reads as a tribute to open-ended exploration and a welcome invitation to step back from intensely goal-oriented ways of life.

Although the kingfishers themselves are described in vivid detail, this book’s strength lies in its equal interest in the lives of other, less immediately striking birds. Narratives woven around the central quest follow pairs of grey wagtails, goosanders and great spotted woodpeckers, with a quality of attention that ensures the unique traits of each are displayed. Gently but persistently, Murphy asks us to recognise and value the presence of these species more fully. Too often, he notes, “We look, but we do not see; what’s more, we notice but often do not remember.” There’s an inviting warmth to his observations of each pair as they build a nest and raise their young. Bird couples appear almost human, with the small dramas of their courtship and co-parenting becoming reminiscent of our own lives. This attentiveness is contagious—it would be difficult to read the book and not see birds in a new light.

There’s a clear-sightedness to Murphy’s observations that any budding naturalist could learn from. Despite the obvious depth of the author’s knowledge, room is left in The Spirit of the River for the unexpected and for behaviour that differs from what’s written in birders’ guides. As an Irish birdwatcher whose book-learning regarding certain species has come from British sources, Murphy is sensitive to local variations, repeatedly asking how the expected behaviour of a species might be changed in the landscape of the Wicklow Mountains. And when he finally finds the kingfisher nest sought after through the book’s early chapters, its location is delightfully unlikely.

In a turn that takes place late in the book, however, this same clear-sightedness and generous attention to detail hits a snag as Murphy introduces a narrative around allegations that lead to multiple trips to court. While great detail continues to decorate his encounters with animals throughout this conflict—we see the kingfishers startled by his ringing phone; the anxiety of and around his beloved Dalmatian during visits to the Garda station; even the unexpected comfort found in conversations with Gardaí about local birds—no detail is presented regarding the nature of the allegations themselves. Aside from the confusion such a marked shift in prose style may cause a reader, there is a worrying aspect to this opacity and to Murphy’s sometimes-disparaging treatment of the court process. For a reader unaware of the facts of the case, it’s difficult to engage with the hurt and frustration that mark these passages, and just a year after the hashtag #BirdingWhileBlack went viral following a May 2020 incident in Central Park—wherein a white woman called the police after observing a black birder—the inclusion of this narrative without greater clarity feels lacking also in a certain level of civic awareness. If personal or legal sensitivities prevented the story from being shared more openly, it may ultimately have been better left out.

Nonetheless, beyond this difficult stretch, the book as a whole offers its readers a journey rife with wildlife, wonder and the warmth of human impression. Although the focus remains on non-human animals throughout, Murphy makes reference many times to the friends, family, mentors and acquaintances whose loving attentions, either to the natural world or to Murphy himself, enable his quest. Despite the feelings of isolation he describes at being a person so wholly committed to the natural, rather than man-made world, the people who weave in and out of the scene—the parents who built nature tables and other instruments for him as a child, the fellow bird lovers who provide life-sustaining peanuts for woodpeckers—are a subtle but ever-present community that seems built on respect and care. In a thoughtfully written foreword by young environmentalist Lilly Platt, as well as in tender scenes between Murphy and his own children, we see this community grow to encompass a new generation. It’s on human connections like these that the natural world depends, if we’re to preserve what wildness is left. Books like Murphy’s, with its affable, easy-going prose and affectionate attention to the world around us, serve not only to entertain, but to remind us: “Despite the gulf that separates us, we may have more in common than we think.”

The Spirit of the River is available to purchase from the publisher, The Lilliput Press.