Entropy and Hope in Death Valley

by Anindita Sengupta

Salt and wildflowers, snow and sand. A sense of depth, of deep, of lowness. In Death Valley National Park, I was aware of constantly traveling on land that once wasn’t land. At some point in the Pleistocene era, the valley held water, large lakes that swooshed about (I imagine) or rippled in giant swirls carving the rock around them. In Death Valley, time is everywhere, a physical presence as manifest as the warm air which is continually recycled, rising to be trapped by the high valley walls and falling to the valley floor like a white scarf, and rising again.

My family was out of time. It was the spring of 2016, and my student visa would be up in a month. We had been in the US for 18 months. My husband had a job. We had applied for a visa and made a home. But bureaucratic immigration systems in the US mean that between each visa there are interviews, wait times, queues. While we waited, we would effectively be without a fixed home. Without address. We would have to get on a plane to India and wait for the approval. It could take months. We didn’t know whether to keep our rental. To pack, store or throw away our belongings. Where we would live in India in the interim. These uncertainties traveled with us to Death Valley.

We reached late, checked in. After dinner, we sat in the balcony, winds shushing around us like ocean sound. As if any moment a fish would appear, beached. We sat and talked in low voices. Behind us, in the lamp-lit room, our child slept. Sometimes, home is a child sleeping on a bed, comfortable.

Death Valley was full of new words for me. Foehn winds blow over the mountains. A virga is a streak or shaft of precipitation falling from a cloud. It disappears before reaching the ground through evaporation or sublimation. Much rain here is virga.

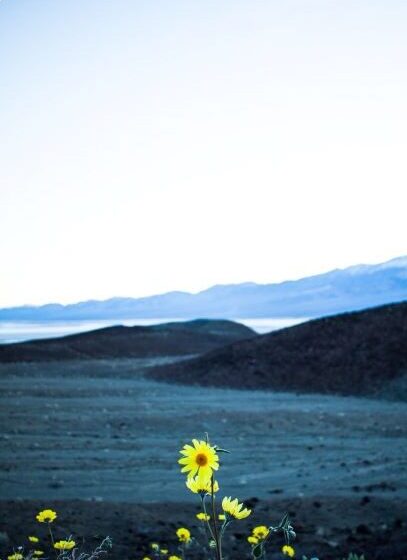

The next day, yellow blooms. Dante’s View is a peak that is part of Mesozoic volcanoes created when the surface of the earth was being stretched, forming a horst or grabens, ruptured crust, lava. Now it contained brimming eyefuls of golden yellow wildflowers called Desert Gold. People around me sighed at the panoramic vista, but I was drawn to an individual flower, filled with a kind of loneliness. I turned to photograph it from different angles. Flourishing here in this land. As have people.

The valley has been home for millennia to the Timbisha tribe of Native Americans, earlier known as the Panamint Shoshone. The Timbisha name for the valley, tümpisa, means ‘rock paint.’ So much more hopeful than death. It speaks of the red ochre paint that comes from a clay found here. Some families continue to live here, at Furnace Creek, which is like a hub for visitors.

The wildflower “super-bloom” that year was a rare event. It takes perfect conditions—“well-spaced rainfall throughout the winter and spring, sufficient warmth from the sun, lack of drying winds.” It was just starting when we were there. We were lucky.

We drove from one part of the land to another in a battered blue used SUV. It felt lighter than it looked, and it had carried us for a year. It was all we could afford. We did not think of it as unreliable, because such categories of difference exist only when one has a choice. We had a car; we piled into it. The unspoken of “maybe we’ll never see this again” hung between us. There were patches of Desert Gold. Mariposa Lily. Other stretches were stark and unfamiliar, gloaming like an alien planet. Enchanted desert. I stared at white land and thought I would like to come back every year. In another moment, walking between steep rocky ridges, I felt an unbearable weight. I would never want to come back, I thought, because some places are meant to be seen only once.

In the sand dunes of Mesquite Flats, my daughter tumbled and played. Snakes buried under, rattling. Possibly.

I hungered at the salt flats.

The miles of them which remained as the area turned to desert and water evaporated. How we associate salt with thirst. How the heart associates distance with home. I had only ever seen salt pans by the ocean, but here salt lay disassociated from water. A thing in itself, divorced from its origin. I felt as if a whisper ricocheted in that vast landscape, the whisper being forget where I come from.

All over Death Valley, I read later, there are springs and ponds, the Death Valley Pupfish. A remnant of the wetter Pleistocene climate. A reminder. There are oases here, home to tiny fish. Refuge.

On our last day there, we thought of driving out via the ghost town of Ballarat, but on a washed-out stretch of gravelly dirt road our car rattled over stones, their clatter ominous, then wheezed to a stop. My husband tried and tried again. Small broken noises. Deafening quiet.

It was just past noon, the sun magnificent in the sky. Only a tiny portion of Death Valley has cell phone reception. We were not in this area. Our phones were useless.

Things I thought of: bread, cheese, bananas (food in the car); water (six small bottles); knitting, books (entertainment for me); crayons (entertainment for my daughter).

We settled in to hail passing cars. There was one every half hour or so. We stopped three or four, asked them to contact a ranger. They assured us they would. We took it on faith. Nobody offered us a ride and we did not expect one. We took turns estimating how long help would arrive in. I aimed at knitting 12 inches before help arrived, then 18 inches.

Death Valley lies in the rain shadow of four mountain ranges. Moisture moving inland from the Pacific Ocean must pass over these mountains. Most of it falls in the mountains as rain. Usually, there is nothing left for the valley. Dry air made me understand thirst as something new, a live animal in my throat. I counted the bottles of water again.

Our daughter, almost four, tried to sleep in the backseat. I used some water to wash her face and neck. A high of 134 °F (56.7 °C) at Furnace Creek is the highest ambient air temperature ever recorded on the surface of the Earth. I tried not to think of this. She was ok. I did not believe we would die there in the desert.

It is possible to die in the desert. Every year, GPS units send people across the desert where no road exists. In the last 15 years, at least a dozen people have died in Death Valley from heat-related illnesses. The area of Death Valley is about 3,000 sq mi (7,800 km2). What does it mean to become lost in that much land?

Help arrived at around 4pm, about an hour before sunset. The cop (not a park ranger, because we were officially outside the national park) said there had been three or four calls about us. We were taken to a motel in the desert, cheap and basic, but it had cell phone signal. We let our daughter make a meal of fries and ice cream. We fell asleep in the hot room, an exhausted sleep, and woke after dark when the tow truck arrived. We drove back to the same spot to pick up the car.

The desert is unearthly and silent at night. The stars overhead, a revelation. I think it unnerved Sam, the driver of the tow truck, because he turned up the music and jigged about in his seat. He didn’t want to talk so we sat in silence, except for the music, for two hours, bumping along, the towed car hulking behind us. When we reached Ridgecrest, a town with lights and shops and grocery stores, I laughed. Even Sam seemed to thaw. “We even have a Hilton,” he said.

At the garage the next day, they said the car was too gone for repair. Better to sell it for scrap. We left it there, took a cab to Los Angeles. A few weeks later, we took a plane to India.

We would come back on a temp visa after four months of waiting in temp apartments. We would come back to fireworks and watch with bleary, jet-lagged eyes.

Four months later, we would get our three-year visa on the same day that a new president was sworn in. Someone would weep to me on the phone. Another person would text me saying welcome to this country, her voice bitter about what the country had become. I would remember Death Valley and hope to find small, yellow wildflowers and fish in the entropy.

We never made it to Ballarat. Later, I read it has one resident. That once upon a time, Charles Manson and his family lived in a ranch near the town. That a hippy celebration there led to 200 people contracting Hepatitis A from contaminated water. These are the ways a place filters through in news items, in outstanding facts of crime and disease.

When I think of the car, it still stands in the desert as if frozen in time, a battered blue SUV surrounded by brooding land.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_Valley

http://www.ohranger.com/death-valley/geology

https://www.nationalparks.org/explore-parks/death-valley-national-park

https://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/nature/wildflowers.htm

Anindita Sengupta is a poet and writer from India. She is the author of Walk Like Monsters (Paperwall, 2016) and City of Water (Sahitya Akademi, 2010). Her work has appeared in several anthologies and journals such as Plume, 580 Split, One, Asian Cha, Breakwater Review and others. She is Contributing Editor, Poetry, at Barren Magazine. She has received fellowships and awards from the Charles Wallace Trust, the International Reporting Project, TFA India and Muse India. She currently lives in Los Angeles, California. Her website is http://aninditasengupta.com