The Voices of the Trees

Mountain Truths

John Muir was born in Dunbar, Scotland, in 1838, and died in Los Angeles on Christmas Eve, 1914. His father was a strict Presbyterian, and required him to learn a certain number of Bible verses every day, on peril of a whipping. By the time Muir was eleven, he had “about three-fourths of the Old Testament and all of the New by heart and sore flesh.” He continued to read the Bible deep into old age. Nonetheless, the lean sinewy man with the bright blue eyes and the long reddish beard can more easily be seen as a wandering monk or nature mystic than as the reputable scion of an evangelical church.

As a young man, Muir walked from Kentucky to Florida, keeping a journal along the way. He arrived in California in 1868, and became a noted writer, botanist and conservationist, working to create Yosemite National Park, and founding the Sierra Club. All his life he remained curious and adventurous, brimful of gusto and enthusiasm. Though he loved his wife and daughters, and was a loyal friend, he also found great pleasure in his own good company, whether taking a sled-ride down a glacier, slipping behind the rushing water of Yosemite Falls, or climbing a Douglas fir in the midst of a tremendous storm. There was no such thing as solitude as far as he was concerned: even when he was tramping the Sierra on his own, the rocks and trees and waters were a shining company of friends.

“Plants are credited with but a dim and uncertain sensation,” he wrote, “and minerals with positively none at all. But … may not even a mineral arrangement of matter be endowed with sensation of a kind?” He thought of rocks as having a certain gentle interiority or “instonation,” and suggested that instead of walking on them as “unfeeling surfaces,” we should instead regard them as “transparent sky.” Whether rocks spoke to him with “audible voice” or “pulsed with common motion,” he was eager to listen and translate, to spell out some of the “mountain truths” he had discovered.

Muir was known in human company as a non-stop talker, and it makes sense that he’d converse with plants and flowers, too. “When I discovered a new plant, I sat down beside it, for a minute or a day, to make its acquaintance and try to hear what it had to say.” At times, he would conduct a regular interrogation. “I said, how came you here? How do you live through the winter? And the plants revealed their secret …” Nor were his encounters always so sedate. A missionary friend in Alaska remembered Muir running from one cluster of flowers to another, falling to his knees in an ecstasy of admiration, as he greeted each new bloom in a mixture of scientific nomenclature and delighted baby talk, all in a broad Scots accent.

The Calvinists of his youth would have disdained such giddiness, seeing the glories of the natural world as fated for destruction, and Muir’s exuberance as an offense against the Lord. But Muir himself had long since cast off such gloomy tenets, imagining a wild heart like his own in every cell and sparkling crystal, and addressing plants and animals as “friendly fellow mountaineers.”

He brought such imaginative identification to larger species, too, remembering individual trees with great precision, well able to distinguish “the sharp hiss and rustle of the wind in the glossy leaves of the live-oaks [from] the soft, sifting, hushing tones of the pines,” and to orient himself, even at night, by the sounds of the wind as it played through the pine needles. There was no end to his attentive listening, or his willingness to be delighted and astonished.

“As long as I live,” he wrote, “I’ll hear waterfalls and birds and winds sing. I’ll interpret the rocks, learn the language of flood, storm, avalanche.” Or, as he scrawled in the margin of one of his favorite books, not the Bible this time, but a volume of Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Between every two pine trees there is a door leading to a new way of life.”

The Voices of the Trees

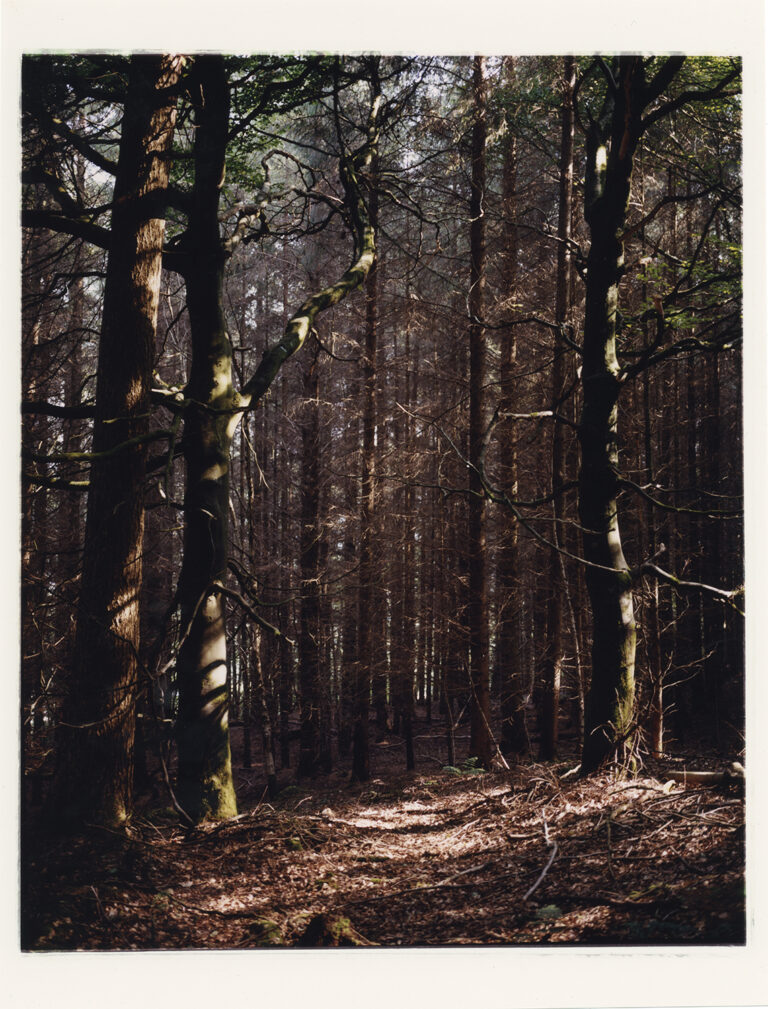

I was wandering the grounds of a big New England estate, following my feet along a quiet track. The trees were looming presences up ahead, their branches inclined towards each other, shifting a little with the wind. It was as if they were talking together, trading intimacies. For a moment, I could almost make out words. But when I paused beneath them, looking up, the trees turned abruptly silent. A flicker of irritation moved among the leaves. It was as if I had burst upon them unannounced—as if, somehow, they hadn’t heard me coming, and my small human presence were an annoyance, an intrusion. I watched as they drew back into themselves, calm and reticent, back into their towering self-sufficiency.

Can one make friends with trees, listen in on their private conversations? Thoreau thought one could. He himself maintained steady friendships with particular trees, often tramping “eight or ten miles through the deepest snow to keep an appointment with a beech tree, or a yellow birch or an old acquaintance among the pines.” In his essay, “Walking,” he describes the “admirable and shining family” who had settled in the pinewood on Spaulding’s Farm. When the wind died down, Thoreau could hear “the finest imaginable sweet musical hum—as of a distant hive in May,” which for him was the sound of their thinking.

As naturalists know, every species of tree has its own distinctive voice, responding differently to wind and rain and snow and shining sun. Thomas Hardy writes of this in Under the Greenwood Tree, allocating subtly different verbs to fir and holly, ash and beech. “At the passing of the breeze, the fir-trees sob and moan no less distinctly than they rock; the holly whistles as it battles with itself: the ash hisses amid its quiverings, the beech rustles while its flat boughs rise and fall.”

John Muir was alert to such distinctions, too. In The Mountains of California, he describes a fierce wind-storm in the Sierras, when he happened to be exploring one of the tributaries of the Yuba River. “Even when the grand anthem had swelled to its highest pitch, I could distinctly hear the varying tones of individual trees—Spruce, and Fir, and Pine, and leafless Oak … Each was expressing itself in its own way—singing its own song, and making its own peculiar gestures …”

It was on this occasion that Muir climbed to the top of a hundred-foot-tall Douglas fir, clinging there for several hours “like a bobolink on a reed,” while the tree flapped and swished and bent and swirled, “tracing indescribable combinations of vertical and horizontal curves.” Muir felt sure of its resilience, and exulted in everything he saw and heard, from the “shining foliage” to the “profound bass of the naked branches and boles booming like waterfalls; the quick tense vibrations of the pine-needles … the rustling of the laurel groves in the dells, and the keen metallic click of leaf on leaf …”

Years later, traveling in Alaska, he built himself a vast bonfire in the midst of a pelting storm. His missionary friend was baffled, as were the local villagers. But Muir made no apologies. He was sacrificing the lives of some few trees to attend more fully to the rest. He simply wanted to observe how those Alaskan trees responded to the wind and rain, “and to hear the songs they sang.”

The Inside Story

“Have you ever tried to enter the long black branches of other lives?” asks Mary Oliver,

tried to imagine what the crisp fringes, full of honey, hanging

from the branches of the young locust trees, in early morning, feel like?

Until very recently, most of us would have had to say no. However much we might enjoy our daily walks, perhaps returning again and again to a particular tree, we had very little notion of how that tree itself might feel. But the publication of Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees in 2016, and David George Haskell’s The Songs of Trees in 2017, followed swiftly by Richard Powers’ bestselling novel The Overstory (2018) and Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree (2021), has brought a welcome infusion of both scientific and imaginative understanding. Listening to trees, it turns out, involves far more than psithurism (the deliciously onomatopoeic word for the rustlings of their leaves and twigs and branches). There is an inside story, too. Early in the spring, just before the leaves open, water pressure builds up inside the trunk, giving rise to a continuous soft murmur. “If you place a stethoscope against the tree,” says Wohlleben, “you can actually hear it.”

Trees too are capable of “listening,” both to one another and to the world around them. Because they extend such a long way underground, the roots of neighboring trees inevitably intertwine. This allows trees to communicate through the roots themselves and through the fungal networks at their tips, “crackling quietly at a frequency of 220 hertz.” Although such signals travel fairly slowly—at about a third of an inch a minute—they are nonetheless extremely effective, allowing trees to warn and protect and even feed each other. Wohlleben writes of mother trees that recognize and defend their younger kin, as well as ancient trunks still green and growing, nourished by the circle of their own great-grandchildren. In general, trees communicate mainly with their own kind. But they can reach out to other species too—Douglas-firs sustaining birches, oaks helping pines—linked by a collaborative intelligence known as the wood wide web.

One of the most lyrical tree interpreters is Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation (originally from the Great Lakes). For her people, the land itself is animate, as are fire, water, chipmunks, orioles, even a single strawberry. Trees, especially, are recognized as teachers. “In the old times, our elders say, the trees talked together. They’d stand in their own council and craft a plan.”

Like Wohlleben, Kimmerer believes that the “standing people” do indeed communicate among themselves, and unite in mutual defense. “We don’t have to figure everything out by ourselves,” she writes. “There are intelligences other than our own, teachers all around us.” And to this day, she goes to them for solace.

I come here to listen, to nestle in the curve of the roots in a soft hollow of pine needles, to lean my bones against the column of white pine, to turn off the voice in my head until I can hear the voices outside it: the shhh of wind in needles, water trickling over rock, nuthatch tapping, chipmunks digging, beechnut falling, mosquito in my ear, and something more—something that is not me, for which we have no language, the wordless being of others in which we are never alone.

After the drumbeat of her mother’s heart, she writes, “this was my first language.”

Footnotes

Mountain Truths

“Plants are credited…” Frederick Turner, John Muir: From Scotland to the Sierra (Canongate, 1997), p. 153.

“instonation…unfeeling surfaces… transparent sky…” Turner, ibid., p. 191.

“When I discovered…” John Muir, The Unpublished Journals of John Muir, edited by Linnie Marsh Wolfe (University of Wisconsin Press, 1979), p. 69.

“I said, how came you…” Turner, ibid., p. 179.

“friendly fellow mountaineers…” Turner, ibid., p. 182.

‘the sharp hiss …” Trevor Cox, The Sound Book: The Science of the Sonic Wonders of the World (W.W. Norton, 2014), p. 181.

“As long as I live…” Cox, ibid., p. 247.

“Between every pine tree…” Cox, ibid., p. 193.

The Voices of the Trees

“eight or ten miles…” Henry David Thoreau, Walden or, Life in the Woods, (Signet Classic,1960), p. 178.

“admirable and shining family…” Henry David Thoreau, Excursions (Corinth Books, 1962), p. 208.

“At the passing of the breeze…” Thomas Hardy, Under the Greenwood Tree (Penguin, 2012), p. 3.

“Even when the grand…” John Muir, The Wild Muir: Twenty-two of John Muir’s Greatest Adventures, selected by Lee Stetson (Yosemite Association, 1994), p. 111.

“like a bobolink …’ John Muir, ibid., p. 112.

“trancing indescribable combinations…” Muir, ibid., p. 112.

“Shining foliage… profund bass…” Muir, ibid., p. 113.

“and to hear…” Turner, ibid., p. 255.

“If you love it enough…” Philip Shepherd, New Self, New World: Recovering Our Senses in the Twenty-First Century (North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, CA), p. 105.

The Inside Story

“have you ever tried…” Mary Oliver, West Wind: Poems and Prose Poems (Houghton Mifflin, 1997), p. 61.

Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate (Greystone, 2015).

David George Haskell, The Songs of Trees: Stories from Nature’s Great Connectors (Viking, 2017).

Richard Powers, The Overstory (W.W. Norton, 2018).

Suzanne Simard, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest (Knopf, 2021).

“If you place …” Wohlleben, ibid. , p. 58.

“crackling quietly…” Wohlleben, ibid., p. 13.

“wood wide web…” Wohlleben, ibid., p. viii. The phrase was apparently coined by Suzanne Simard.

“In the old times…” Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Milkweed Editions, 2013), p. 19.

“We don’t have to figure…” Kimmerer, ibid., p. 58.

“I came here to listen…” Kimmerer, ibid., p. 48.

“this is my first…” Kimmerer, ibid., p. 48.

Christian McEwen is a freelance writer and workshop leader, originally from the UK. She is the author of several books, including World Enough & Time: On Creativity and Slowing Down, now in its eighth printing. She is currently working on a book called In Praise of Listening, from which these excerpts are taken. www.christianmcewen.com